“It takes a lot of creativity, creativity in [finding] the resources, when researching remotely,” said Kerry Rork, a senior majoring in Political Science. Rork works on the Dictionary of Art Historians (DAH). At first glance, it may seem unusual for a political science student to work on an art history research project, but Rork has been working on the project since her first year at Duke.

The DAH serves as a database of the major art historians in the Western world. The project is led by Lee Sorensen, the Reference Librarian for Visual Studies and Dance at Lilly Library. The DAH has been in development for over 35 years and has been associated with Duke University since 2010. In 2016, the DAH became part of the Digital Art History & Visual Culture (DAHVC) Research Lab, formerly known as the Wired! Lab, since 2016.

The DAH is a valuable tool for art historians and students alike. As Sorensen pointed out, “Anytime you’re writing about the past, you’re putting a slant on it. The slant you’re putting on it is what you think is important and context from the time period in which it was written so it makes sense to readers, but that context gets lost.” Students creating entries for the dictionary find this context.

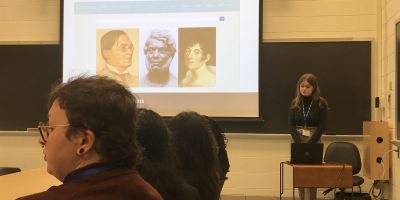

While searching for the context, some students find venerable stories from the lives of art historians. Eleanor Ross, a sophomore working with the DAH, wrote about the espionage of Rose Valland during WWII. Valland, pictured to the right, is just one example of the art historians whose histories are made richer by understanding their context.

During the COVID-19 lockdown and restrictions, the DAH was also able to give undergraduates the opportunity to conduct research. Denise Shkurovich, a pre-medical student majoring in biology, said she would have ordinarily been working in a typical wet lab, carrying out biomedical projects. Instead, pandemic restrictions led her to the DAH. As most research on campus was shutting down in March 2020, the DAH was moving full steam ahead.

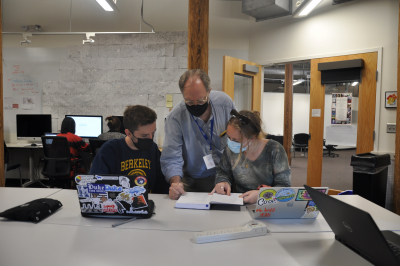

As a humanities research project, students were able to shift towards relying on electronic databases and scanned resources from the Duke University Libraries and peer institutions. Rork said that even though she missed the collaborative space in the DAHVC Research Lab, the shift to remote work didn’t stop her ability to do research. Over her four years, the DAH has left her with several valuable lessons about research that go far beyond the field of art history. While they were unable to request physical copies of sources from various institutions, Rork and other students had to learn to communicate with librarians and faculty at peer institutions.

Even when not operating in the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, learning to communicate is a skill central to the research experience, and it’s a skill that many undergraduates don’t realize is part of academic research. One student, Paul Kamer, spent this past summer cataloging German historians. As someone who doesn’t speak German, Kamer had to learn to communicate with Sorensen about the results from online translators. From this, Kamer learned from Sorensen how to deal with ambiguities and criticisms, which ensures the end product is the best it can possibly be.

For many undergraduates, the most valuable part of a research experience is the development of communication and professional skills. Several students pointed to Sorensen’s mentorship as central to this aspect of their experience at the DAH. Helen Jennings, a junior majoring in art history, noted that Sorensen always wants to make sure that students are passionate about the work they’re doing, and that they understand its place within a broader context.

Lindsay Dial, a sophomore working on the DAH project, advised her peers to “start early, and talk to your professors early, especially the ones you think you’d be interested in doing research with.” Other students echoed these sentiments, and pointed to the value of the resources for undergraduate research at Duke. Many students found the DAH through Duke’s FOCUS program, or the MUSER program, which promotes equity in access to research opportunities.

Moving forward, Sorensen wants to spend more time orienting the DAH towards equity and diversity. About women, Sorensen pointed out, “Women were under-represented in the literature even though they were some of the most important early producers in the field.” Further, art history research is heavily skewed towards European and/or English-speaking historians. In future updates, the DAH is aiming to include more marginalized art historians. About the shift, Sorensen said, “You have to have goals, and you have to make the research relevant to the times.”

The Fall 2021 edition of the dictionary included several entries working towards these goals. One such entry highlighted Alain Locke, the first Black man to receive a Rhodes scholarship. In addition to his editorship at The New Negro and his studies in philosophy, Locke was a scholar of African, Black, and European art.